Rippling water drop, copyright iStockphoto.com/deliormanli

It’s been a rainy week in New York City, and my office next to our front porch and my container garden has me thinking about that ubiquitous wetness. It’s been soaking my plants, and after a quick errand on Friday afternoon, its dampness lurked for hours on the hem of my jeans.

It’s easy to take the wonder of water for granted because it’s everywhere, but its physical properties are anything but ordinary. Almost all solids of any substance are more dense than their liquid counterparts. But if ice were more dense than liquid water, ice cubes wouldn’t float in cool drinks on a summer day. Ice wouldn’t freeze at the tops of cold lakes (no ice skating), and polar ice caps would be more like suboceanic ice cushions. If water were a normal liquid, the Earth would look really weird.

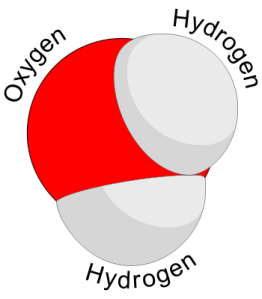

Water molecule, via Wikipedia/Booyabazooka

The molecule itself is bent, lending hexagonal elegance to snowflakes. In a liquid the molecules glom to each other, not quite like superglue. But that watched pot (that seemingly never boils) needs lots of energy to release water into steam.

For those of us who’ve built molecules for a living, water is often our enemy, something that can get in the way and keep the right components from getting together. But Nature incorporates water beautifully, using the molecule as a structural tool and as a critical player in the reactions that make life work. Forced to take some tricks from Nature in my own graduate work (my highly charged molecules wouldn’t dissolve in any other solvent), working in water was like learning a related foreign language. I learned some basic grammar and vocabulary, but fluency of water chemistry is a challenge beyond the synthetic lab. By Nature’s standards, I was, perhaps, third rate.

I missed the AMNH’s exhibit on Water when it was in NYC (but I think it’s still touring, check your local science museum). As climates change, ice melts, sea levels rise, more intense storms brew in the oceans, water sits at the heart of the environmental challenge. According to the World Health Organization, as of 2002, nearly 20 percent of the world’s population didn’t have access to healthy, sanitized drinking water supplies.

Three atoms hooked together connect to the inner workings of life, health, the environment and public policy.

Subscribe to RSS Feed

Subscribe to RSS Feed